The Impact behind “Indigenuity”

When Dawn Pratt sees a tipi, she also sees a spaceship.

“It’s the most aerodynamic shape,” says Pratt, a member of Muscowpetung Anihšināpē Nation and a STEM educator who lives in Saskatoon. “I was just blown away by thinking about the tipi and how it’s designed perfectly, so much so that the shape is employed in spaceships.”

Pratt has always been fascinated by math and science, especially chemistry (she vividly remembers getting a chemistry set as a gift from her parents when she was a kid). After earning her master’s degree in chemistry—with a focus on the use of organic absorbent materials to remove arsenic from contaminated water—she worked in several teaching roles before launching her own education company, which develops and teaches Indigenous STEM lesson activities, in 2020.

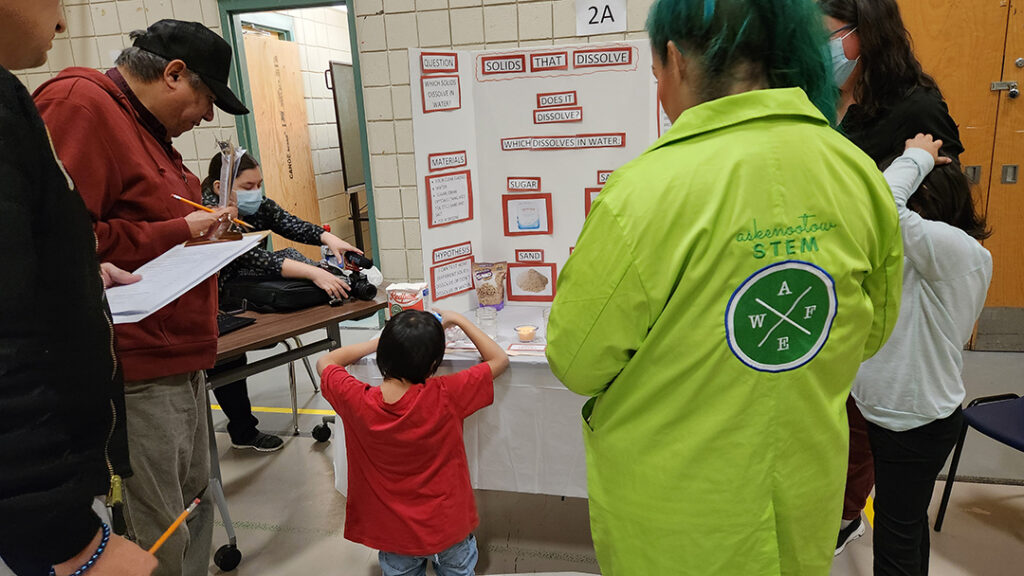

“I kept seeing big gaps in our education system, or going to a science centre and not seeing Indigenous [technology],” says Pratt. “I like to Indigenize my content.” She named her business askenootow STEM Enterprise in honour of her great-great-great-grandfather, a translator who spoke Cree, English, and French. The Cree term askenootow means “Earth workers” in English.

It’s important to Pratt to integrate Indigenous, Elder, and Knowledge Keeper teachings into her work. “I started working alongside a Knowledge Keeper […] and I realized that he was very observant, something we use in science.” She also discovered how often traditional expert knowledge and cultural teachings fit in with current scientific research. For example, she says the star people teachings found in many First Nations creation stories align with recent analyses of ancient meteorites, which have revealed that the chemical components needed to form DNA—and life—may have arrived on Earth with them.

Pratt’s Indigenized science content teaches about everything from using coding in beadwork to the natural chemical processes at work in tanning hides, and even what a robot chicken pow wow dancer looks like.

Land-based and hands-on learning is a definite focus of Pratt’s work. For example, in learning about the technology of tipis, she says: “We build miniature tipis and talk about the math. We talk about what tools Indigenous people had available to measure the base of a tipi so they could figure out how far apart their poles need to be, how many poles they need, how they go on the tipi, the importance of triangles, and just how aerodynamic it is.”

Left: Dawn Pratt and her daughter Cianna building an igloo at the Saskatchewan Science Fair Indigenous Indigenuity Exhibit. Right: Pratt delivers a canoe presentation at Starblanket First Nation for SIIT and L3 Harris Indigenous Dreamers Doers Innovation Camp

Hands-on learning offers a tactile approach that isn’t always available in the classroom. And it’s not just for tipis. As an engineering activity, students were tasked with figuring out which shape of canoe offers the best combination of stability, strength, and speed. They made miniature versions with simple materials and then attempted to float them with rock weights to see which shape and material performed best. In another lesson, the jawbone of a buffalo, its teeth intact, was passed around the group to facilitate a discussion about herbivores, carnivores, and omnivores.

Ultimately, says Pratt, Indigenous knowledge and worldviews, including spirituality, can bring balance to Western STEM, which, Pratt notes, “tries to be objective—but it’s not as objective as it likes you to believe it is.”

For Pratt, learning is lifelong. “When I go places, I’m learning. I just learned that the Inuit created their own wetsuits from whale intestines!” she says, proposing that we coin a word to describe Indigenous ingenuity: “Indigenuity!”